In the name of Koran (Talibes in Senegal)

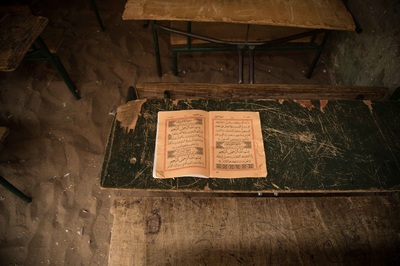

This is a project that addresses one of the most important problematics of exploitation of child labor socially accepted, using religious education, in this case koranic, as justification.

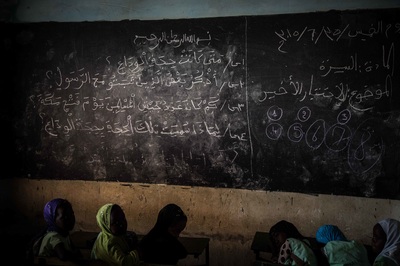

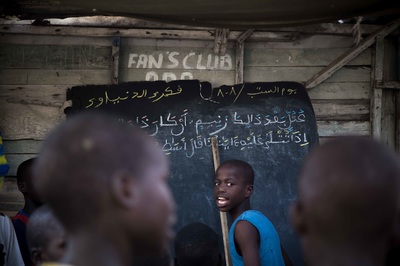

In Senegal, the overwhelming majority of the population (94%) are practicing Muslims. An estimated 90% of Senegalese Muslims are members of Sufi brotherhoods, which place a high value in master-disciple relationships. In line with this tradition, male children as young five are often sent to daaras, Koranic boarding schools where students receive a religious education. Yet, not all daaras are created equal: while some focus on transmitting wholesome Islamic values and beliefs, a great part of those that exist today represent a form of institutionalized child abuse that is tacitly condoned by Senegalese society; which still places prestige in receiving a Koranic education far away from home.

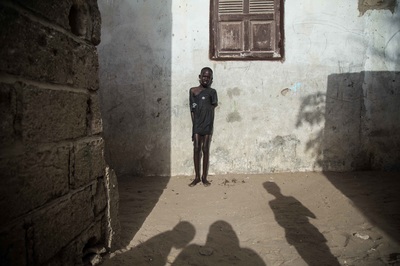

As of 2010, an estimated 200,000 boys had become talibes, term used to refer to children who studies the Quran in Koranic educational institution called Daara. The children are typically entrusted to marabouts, or religious instructors, who in these sadly common scenarios house their charges in derelict buildings. These so-called educational centers accommodate normally from 30 to 100 boys, who are packed into rooms and made to sleep on the floor, often living in squalor. Malnourishment is common, and the standard toilet consists of an empty room with a couple of filthy buckets, which children use to both relieve themselves and bathe.

Despite these conditions, the young talibes are forced to earn their keep – or suffer the consequences. They take to the streets with tell-tale empty cans of tomato sauce, begging for money. These particular cans identify the youngsters as talibes. In Senegal, each group of street beggars resorts to its own receptacle. If the talibes do not return to the daara with the amount mandated by the marabout, they are deprived of meals – or worse, beaten and forced to sleep on the streets.

In Senegal this practice is not seen in the country as cruel or unjust, rather it is accepted as a way to transfer the values of the koran,it is implicitely understood that children must self-finance their education and cover their living expenses of their education.

The young talibes frequently come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, and easily fall prey to unscrupulous marabouts, who use the money collected by children for personal gain. They become victims of a socially-accepted form of child labor, which paves the way to further violations such as mistreatment, beatings and some cases sexual abuse. Those young talibes who rebel against the harsh treatment and run away from their daaras, often end up becoming street children. UNICEF estimates that there are around 100,000 child beggars in Senegal – not including current talibes. But from this number, Understanding Children's Work estimates that 90% of them are indeed former talibes. Local non-governmental organization s such as “Boolo En Faveur Des Enfants” have taken great strides to help these vulnerable children by providing vocational incentives and alternative education, remove and rehabilitate children from the street. Kane Mame Bigue, a sociologist, who is part of the multidisciplinary team, that focuses its efforts and works together with this NGO, said “is a project that proposes to remove and rehabilitate children from the street in general, talibes especially, in perfect synergy with state organizations and organizations of civil society working in the field of child protection”. The NGO operates several halfway houses, such as La Maison Rose, where they shelter and feed the children rescued off the streets as they attempt to get in touch with their birth families. In extreme cases, orphans are placed with host families who help reintegrate the former talibes into society. Working alongside UNICEF and local civil society organizations, the NGO has successfully implemented social programs that monitor existing daaras and ensure these meet certain standards that may guarantee the well-being of their students. But these isolated efforts are insufficient to change this harsh reality It affects many thousands of children in the country.

Text in collaboration with Carla McKirdy.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/03/talibes-senegal/475320/

This is a project that addresses one of the most important problematics of exploitation of child labor socially accepted, using religious education, in this case koranic, as justification.

In Senegal, the overwhelming majority of the population (94%) are practicing Muslims. An estimated 90% of Senegalese Muslims are members of Sufi brotherhoods, which place a high value in master-disciple relationships. In line with this tradition, male children as young five are often sent to daaras, Koranic boarding schools where students receive a religious education. Yet, not all daaras are created equal: while some focus on transmitting wholesome Islamic values and beliefs, a great part of those that exist today represent a form of institutionalized child abuse that is tacitly condoned by Senegalese society; which still places prestige in receiving a Koranic education far away from home.

As of 2010, an estimated 200,000 boys had become talibes, term used to refer to children who studies the Quran in Koranic educational institution called Daara. The children are typically entrusted to marabouts, or religious instructors, who in these sadly common scenarios house their charges in derelict buildings. These so-called educational centers accommodate normally from 30 to 100 boys, who are packed into rooms and made to sleep on the floor, often living in squalor. Malnourishment is common, and the standard toilet consists of an empty room with a couple of filthy buckets, which children use to both relieve themselves and bathe.

Despite these conditions, the young talibes are forced to earn their keep – or suffer the consequences. They take to the streets with tell-tale empty cans of tomato sauce, begging for money. These particular cans identify the youngsters as talibes. In Senegal, each group of street beggars resorts to its own receptacle. If the talibes do not return to the daara with the amount mandated by the marabout, they are deprived of meals – or worse, beaten and forced to sleep on the streets.

In Senegal this practice is not seen in the country as cruel or unjust, rather it is accepted as a way to transfer the values of the koran,it is implicitely understood that children must self-finance their education and cover their living expenses of their education.

The young talibes frequently come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, and easily fall prey to unscrupulous marabouts, who use the money collected by children for personal gain. They become victims of a socially-accepted form of child labor, which paves the way to further violations such as mistreatment, beatings and some cases sexual abuse. Those young talibes who rebel against the harsh treatment and run away from their daaras, often end up becoming street children. UNICEF estimates that there are around 100,000 child beggars in Senegal – not including current talibes. But from this number, Understanding Children's Work estimates that 90% of them are indeed former talibes. Local non-governmental organization s such as “Boolo En Faveur Des Enfants” have taken great strides to help these vulnerable children by providing vocational incentives and alternative education, remove and rehabilitate children from the street. Kane Mame Bigue, a sociologist, who is part of the multidisciplinary team, that focuses its efforts and works together with this NGO, said “is a project that proposes to remove and rehabilitate children from the street in general, talibes especially, in perfect synergy with state organizations and organizations of civil society working in the field of child protection”. The NGO operates several halfway houses, such as La Maison Rose, where they shelter and feed the children rescued off the streets as they attempt to get in touch with their birth families. In extreme cases, orphans are placed with host families who help reintegrate the former talibes into society. Working alongside UNICEF and local civil society organizations, the NGO has successfully implemented social programs that monitor existing daaras and ensure these meet certain standards that may guarantee the well-being of their students. But these isolated efforts are insufficient to change this harsh reality It affects many thousands of children in the country.

Text in collaboration with Carla McKirdy.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/03/talibes-senegal/475320/

© Sebastian Gil Miranda Photography - All rights reserved